LawSikho + SkillArbitrage: A Contrarian's Guide To Edtech

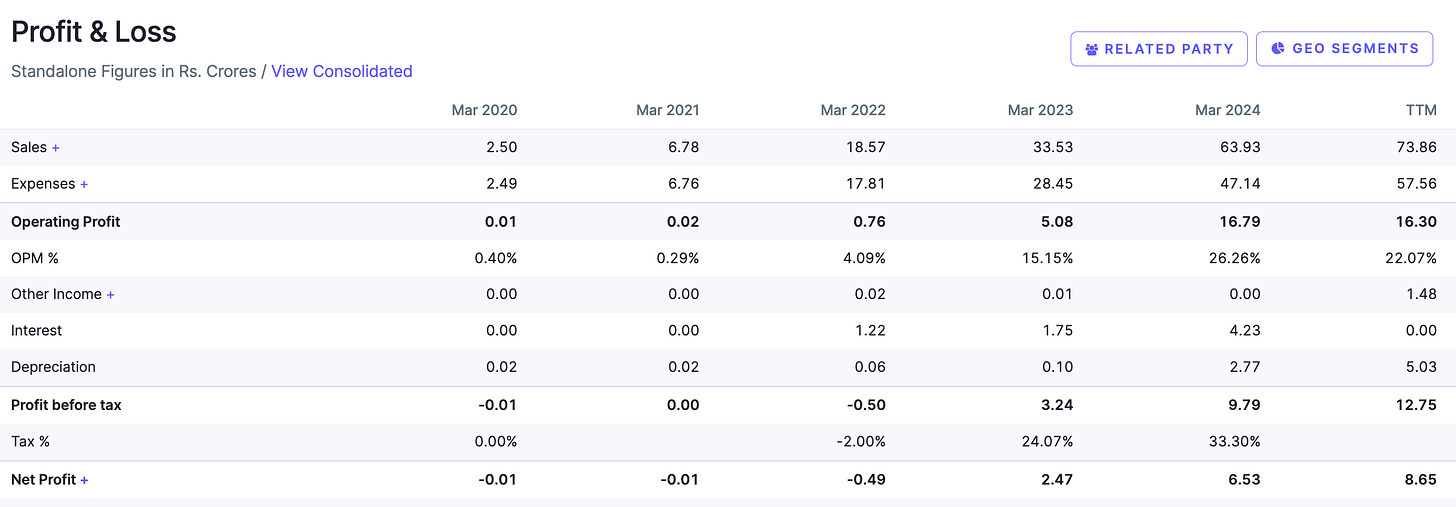

How a couple of law students turned down VC millions, survived a university fallout, and built a ₹300+ crore public company by betting on India's untapped talent.

Imagine an Indian publicly listed 700-employee company with a market cap of Rs 300+ crores that works totally remotely. What are the odds of that being true?

In the ever-evolving landscape of Indian startups, some stories need to be told not because they made headlines, but because they challenge our fundamental assumptions about building businesses in India.

This is one such story.

When I connected with Ramanuj Mukherjee, I was meeting someone who had navigated an interesting life - from a government clerk's son to building one of India's most interesting edtech companies.

The Path to Law: Breaking the First Barrier

Growing up in a government colony in Kolkata, Ramanuj's world was defined by clear boundaries. His father worked as a clerk in the Government of India Press, his mother was a teacher in a high school, and everyone around him worked in government jobs. The message was clear: study hard, get a government job, or face a life of uncertainty.

Ramanuj says, "The environment was very specific. If you were smart, you were expected to become a doctor or an engineer. That was the universal truth. Business meant running a small shop, and you would only do that if you failed to secure a job as an engineer or a doctor or a teacher — it was considered degrading. The concept of startups didn't exist."

Almost accidentally, Ramanuj attended a career counseling event by Law School Tutorials, and he glimpsed a world beyond the conventional narrative. "I came to know there are these national law universities, there are internships, there are big law firms," he recalls. More than that, he saw law as something associated with power and justice—a way to understand and perhaps influence how the system works.

The decision to study law itself was a dramatic departure from the expected path. When Ramanuj announced his intention to pursue law instead of medicine or engineering, it caused such distress that his father broke down crying. It wasn't just disappointment - it was a genuine fear for his son's future.

The First Taste of Digital Business

Ramanuj joined West Bengal National University of Juridical Sciences (NUJS) to study law and it is there that he met his closest friend and future cofounder Abhyuday Agarwal. They became fast friends and would work on projects together and figure out ways to make money.

Ramanuj was studying on education loan. On top of this, NUJS (National University of Juridical Sciences) decided in his 2nd year of college to almost double the yearly fees from Rs 67,000 to Rs. 130,000. His bank refused to increase the loan amount, so he was facing uncertainty about how he will pay for his semester fees.

This led him to a freelance opportunity with IMS Education, then the biggest player in CAT training. What started as a way to earn money became his first lesson in digital business.

Working with IMS, Ramanuj helped build their law entrance coaching product. He was earning between ₹80,000 to ₹100,000 per month as a freelancer, and managing a team of over 20 freelancers he created - significant money and responsibility for a law student. But more importantly, he was learning about product development, content creation, and digital marketing.

The turning point came when he noticed something interesting - IMS's online presence was worse than their competitor's. "LST had a great blog, a forum, all the information, everything was there," Ramanuj says about the competitor. "But IMS, despite being a bigger company with a larger digital marketing team, couldn't match it."

To demonstrate to them how to do it right, Ramanuj built a forum that attracted 4,000 users in a year.

It was his first experience creating a digital platform, and it taught him valuable lessons about community building and user engagement.

The Social Network Effect

But what opened their eyes was not NUJS, but their frequent visits to IIT-Kharagpur!

The entrepreneurial spark in Ramanuj's story came from an unlikely mix of Hollywood and IIT-Kharagpur. "Watching 'The Social Network' was like a revelation," he tells me, his eyes lighting up at the memory. "The idea that you could build something on the internet and make millions of dollars... it was mind-blowing." For a law student in Kolkata, Mark Zuckerberg's story might have seemed as distant as Mars, but it planted a seed.

The contrast between his law school environment and the IIT ecosystem couldn't have been starker. At NUJS, the focus was on securing traditional legal careers. At IIT Kharagpur, students were dreaming of building products and companies. It was during these visits that Ramanuj began to see a different future for himself.

His breakthrough moment came at a Startup Saturday event near his college in Sector 5, where he met a fresh IIT graduate building a data protection software company. "Their office walls were covered with product roadmaps written on sticky notes," he remembers. "It showed me that what I saw in 'The Social Network' wasn't just a movie fantasy - people were actually doing it here in India."

The IIT graduate's office became a kind of prototype for what Ramanuj would later build. While he didn't end up working as their salesperson (though they offered him the role), he found himself regularly hanging out at their office, absorbing everything he could about building a technology company. It was a crash course in startup building, watching first-hand how a team of young IIT graduates was turning their technical knowledge into a real business.

What's fascinating about this period is how Ramanuj, despite his non-technical background, was able to bridge these two worlds. He understood enough about technology to be valuable to these tech founders (he helped them with contracts and legal work), while also learning the fundamentals of building a technology company. It was a perfect example of what he would later master - the art of skill arbitrage.

"I didn't know how to build these things, and I probably wasn't going to learn coding anytime soon," he admits. "But I knew I had to find people to collaborate with." This early recognition - that you don't need to be a technical founder to build a tech company, you just need to understand enough to collaborate effectively - would become a crucial lesson in his entrepreneurial journey.

After graduation, both Ramanuj and Abhyuday landed at Trilegal, one of India's top law firms. "They were not as big back then, but they were already considered one of the top law firms," Ramanuj recalls. At the time he joined, Trilegal had about 140 lawyers, and they were known for something specific - their commitment to paying top-tier salaries.

The Trilegal experience lasted just under a year, but it was formative for both of them. They quit almost simultaneously, with Abhyuday leaving just one month before Ramanuj. They started a business under the banner iPleaders.

The NUJS Years: A Lesson in Institutional Politics

The partnership with National University of Juridical Sciences (NUJS) represents one of the most fascinating chapters in their story - a case study in how traditional institutions grapple with digital transformation, and how institutional politics can make or break partnerships.

The numbers were impressive for those early days - they were hitting ₹50 lakhs in monthly revenue, with the university taking a 30-40% revenue share. It seemed like a win-win arrangement. The university got a significant revenue stream, and LawSikho got the credibility of being associated with one of India's premier law schools.

The university, confident in its brand name and resources, thought it could replicate LawSikho's success independently. They tried bringing in other private players and attempted to launch their own version of the same programs.

This overconfidence stemmed from a fundamental misunderstanding. The university authorities believed their brand name was the primary driver of success. "They were very surprised," Ramanuj recalls. "Everything was selling in their name, so they thought it was all because of them."

What they failed to understand was the complex ecosystem of marketing, content creation, and student services that iPleaders had built.

The relationship became increasingly strained as the university tried to assert more control. They weren't just demanding better revenue terms - they were actively trying to prevent LawSikho from working with other universities.

The breaking point came dramatically. A new vice chancellor was appointed — a retired Chief Justice. A group of teachers complained to him about the online courses being harmful for students(!). Overnight, without warning, all courses were suspended. The impact was immediate and severe - three and a half thousand students were left in limbo, with no certifications and their fees that they had paid were stuck with NUJS. iPleaders also did not receive their dues under the contracts.

What followed was a legal battle that revealed the challenges of dealing with government institutions in India. "They were so arrogant and confident - 'We are the law, who will do anything to us?'" Ramanuj recalls. The university's attitude was emblematic of a larger problem in Indian education - the lack of accountability in government institutions.

The legal process was frustrating. Eventually iPleaders won all legal proceedings after 6-7 years of prolonged litigation. Even when they secured favorable judgments, enforcement was a challenge. There are still some awards and court orders that are pending enforcement in various courts.

Looking back, Ramanuj sees the NUJS episode as a blessing in disguise. While they lost two to three years of hard work, they got out of what he calls "that trap" with the university. More importantly, it proved that their success wasn't dependent on university certification - students continued to enroll in their courses even without it, validating their focus on practical skills and outcomes over credentials.

Focus On Outcomes For Students

The real issue, Ramanuj argues, lies in the incentive structure and who controls these institutions.

"We've created a situation where you can't start a private higher education institute without several crores of investment. A university needs a hundred crore investment in most places in India. Universities and colleges are basically set up by real estate tycoons and politicians because they need a place to invest their black money. This has become the reality of India in many places."

The business model is almost foolproof for these owners. Once you've built a university or college, money laundering becomes easier, and the real estate value appreciates significantly.

"The ROI is much better if it's a university," Ramanuj notes with a hint of irony. "Until now, there's been no real competition unleashed in that sector."

He pulls no punches when describing how this plays out on the ground. These institutions have no real incentive to deliver value to students because their existence doesn't depend on student success. They've already made their money on the real estate play, and the steady stream of students is just an added bonus.

And students really don’t have anywhere else to go.

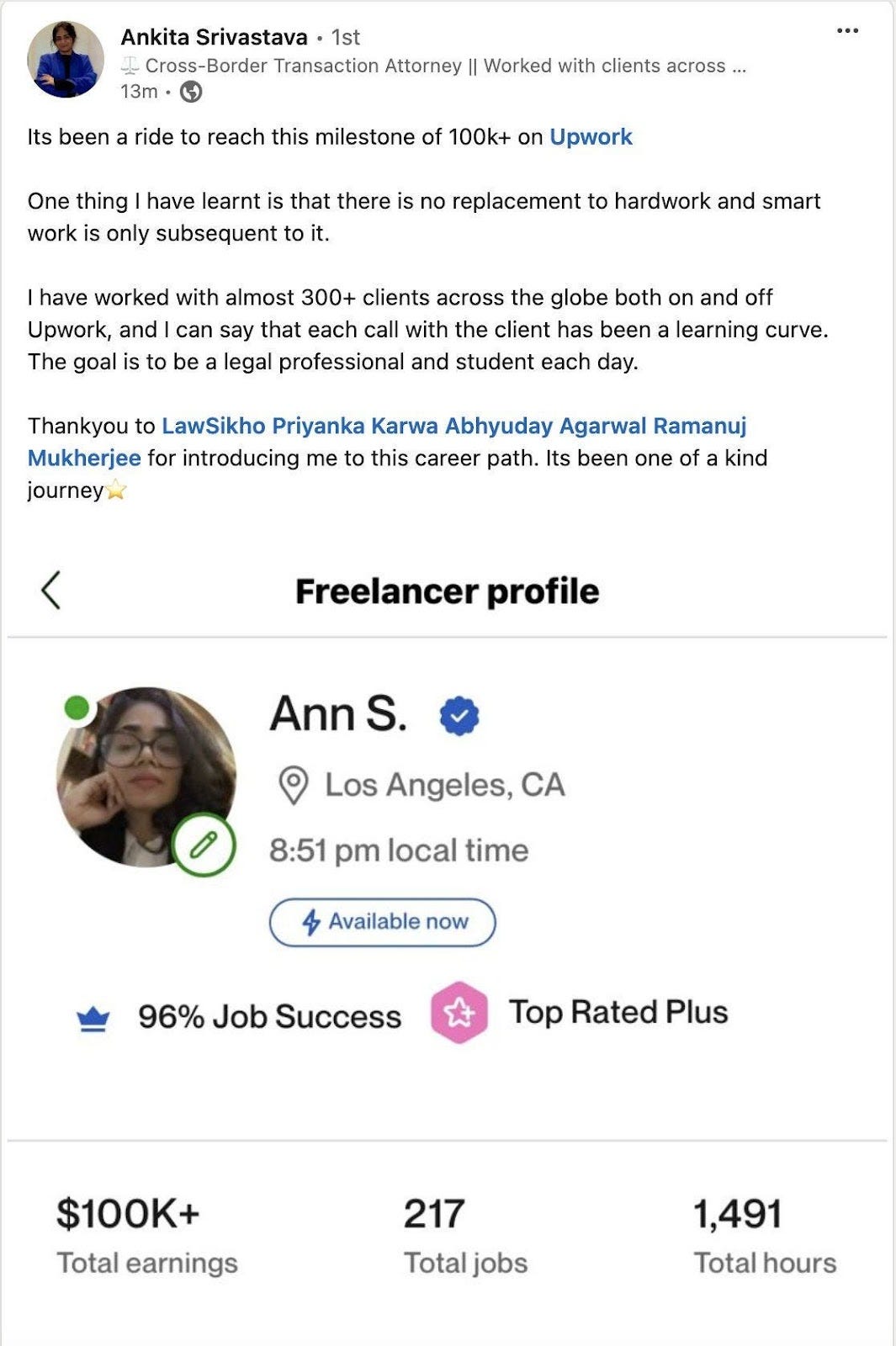

For LawSikho+SkillArbitrage, the focus has been almost entirely on student success and outcomes.

They're now targeting about ₹20 crore monthly revenue, split between upskilling in India (₹10 crore), international markets (₹5 crore), and SMB businesses outside India (₹5 crore).

Building Markets: The Entrepreneur's View vs. The VC Playbook

One of the most fascinating parts of my conversation with Ramanuj was his critique of how VCs think about markets versus how entrepreneurs actually build them.

"If you look at the great companies, they all start off by dominating a very small niche and as you grow, you grow into adjacent markets. Google did that. Facebook did that. Everybody did that."

But today's VC approach, particularly in India, seems to have lost this wisdom. When VCs questioned LawSikho's market size, Ramanuj's response was illuminating:

"That does not make any sense, because you have to understand that even if you start in a very small market, you are always able to grow into other markets."

The disconnect becomes clear when you look at how VCs typically approach market sizing. They want to see a massive Total Addressable Market (TAM) right from the start. They ask for market size calculations, competitor analyses, and growth projections - all of which, Ramanuj argues, are essentially exercises in fiction when you're building something new.

"VCs are good at pattern matching," Ramanuj explains with a hint of irony. "They have their own thesis that they're trying to catch what they think is the next big thing." This approach led to some interesting encounters. In 2015-16, VCs weren't interested because they thought the market was too small. By 2018, when they offered $10 million, it came with strings attached - they wanted LawSikho to stick only to law courses, essentially constraining the very growth they claimed to want.

Ramanuj's approach, in contrast, is more organic and realistic. "How do you say how big the market is? It's all assumptions," he notes. Instead of focusing on theoretical market sizes, he emphasizes the importance of execution in your current market: "How do we know we are doing a good job of saturating that current market? Who's left and how do we saturate even further?"

This philosophy aligns closely with Peter Thiel's idea of starting with a small market where you can become a monopoly and then expanding from there.

LawSikho's journey exemplifies this — they started with law courses, became dominant in that space, and are now expanding into adjacent areas like data science and business skills.

The contrast becomes even starker when you look at their expansion strategy. Rather than trying to capture multiple markets simultaneously (a common VC-backed approach), they've moved methodically.

What's particularly interesting is how this approach has validated itself over time.

When UpGrad offered to acquire them in 2021-22 at approximately ₹175 crore valuation (they declined to sell), it wasn't because they had captured a massive market all at once. It was because they had built something valuable in a specific niche and demonstrated the ability to grow sustainably.

This methodical approach to market building also explains why Ramanuj is skeptical of traditional VC metrics. "How big is the market we are currently serving? That is also very hard to measure," he notes. Instead of focusing on theoretical market sizes, he emphasizes actual customer outcomes.

Ramanuj's perspective offers a valuable lesson for entrepreneurs: don't let VC frameworks dictate your market approach. Start with a market you can genuinely serve well, become dominant in that space, and then use that strength to expand into adjacent markets.

It might not make for the most exciting pitch deck, but it's how real, sustainable businesses are built.

The Remote-First Culture

When I ask Ramanuj about remote work, his response is immediate and unequivocal: "Remote is best."

But what's more interesting is his understanding of why many companies struggle with remote work - it's not the concept that fails, but the implementation.

"People don't learn how to work remotely," he explains, touching on a crucial insight. "They want to replicate how people work in office in remote settings. That doesn't work. You need different systems - everything has to be different."

This observation cuts to the heart of why many Indian companies struggle with remote work. They try to transplant office-based workflows and management styles into a remote environment, essentially forcing square pegs into round holes. LawSikho, on the other hand, has built its systems from the ground up to be remote-first.

The Future: Beyond Traditional Education

As our conversation shifts to the future of education in India, Ramanuj's tone becomes more animated. Having battled the system both as a student and an entrepreneur, he sees fundamental flaws in how higher education operates in India - flaws that create opportunities for disruption.

"Think about this," Ramanuj says, using an example that perfectly illustrates the inefficiency. "A college is a building where people come to study. That building, in my opinion, is wasted because it can double up as a place for work for the same students." He envisions a model where the same infrastructure could serve educational purposes during one shift and function as a workplace during another - something already happening in countries like Germany.

The German model particularly interests him. "In Germany, companies pay for your higher education because you're going to work for them after that, and you're working in the factory while you're getting vocational educationin college," he explains. It's not just theoretical education but practical, applied learning that directly connects to employment.

But perhaps his most radical suggestion is about transparency and accountability. "One master stroke can be that you make sure everybody has audited placement numbers out," he proposes. "Just like you have to file your income tax return, you have to file your placement return for the year. That would be a total game changer."

This simple change, he argues, would force institutions to care about outcomes. "There are enough resources in the institutes to make people job-ready and productive, but they don't care because there's no incentive to actually succeed in that game."

It's this understanding of the system's flaws that shapes LawSikho's approach to education.

Rather than trying to replace traditional colleges and universities, they focus on professional upskilling - targeting those who are already in the industry and need to upgrade their skills.

"We are very different," he emphasizes. "Our data science course will be ₹50,000, but it'll be very different in nature - very specific problems, very specific skills like teaching you how to manage a sales team with this."

Looking ahead, Ramanuj sees opportunities for radical transformation. He's actively looking to acquire a university abroad, particularly in the US, but with a different vision - one focused on practical skills and real-world outcomes rather than just credentials. It's an ambitious plan, but given his track record of challenging established systems, it would be unwise to bet against him.

This vision of education - practical, outcome-focused, and aligned with market needs — stands in stark contrast to the current system dominated by real estate interests and regulatory capture. It's a vision that might seem idealistic, but as Ramanuj has shown throughout his journey, sometimes the most practical solutions come from challenging fundamental assumptions about how things should work.

The Larger Picture

What makes LawSikho's story particularly relevant is how it challenges several assumptions about Indian startups. First, that you need venture capital to build a significant business. Second, that you need to focus on degrees rather than skills. And third, that you need to follow the conventional playbook of Indian edtech companies.

As our conversation winds down, I'm struck by how Ramanuj's journey reflects a changing India. It's a story of how a clerk's son from a government colony could build a company that's challenging traditional education systems. It's about understanding both the ground reality and the bigger picture. But most importantly, it's about building something sustainable and valuable, not just chasing the next funding round or exit opportunity.

In many ways, this is the kind of story that needs to be told more often - not because it fits the typical startup narrative of massive funding rounds and quick exits, but precisely because it doesn't. It shows there's another way to build in India, one that might be more sustainable and ultimately more impactful.